Content

- Auto, Pharma Sectors Cheer GST Slabs; Airlines Say Wings Clipped

- Should Commercial Speech on Digital Platforms Be Regulated?

- India–China: The Making of a Border

- India’s Birth Rate Down: First Dip in TFR in 2 Years

- How the Antibiotic Culture in India Imperils Mental Health

- Logs in Himachal Floodwaters: Supreme Court Response

- New Foreigners Act, 2025

- PVTGs and Enumeration Issues

Auto, pharma sectors cheer GST slabs; airlines say wings clipped

Basics

- GST (Goods and Services Tax): Indirect tax introduced in 2017, subsuming multiple central & state taxes.

- GST Council: Apex decision-making body under Article 279A, chaired by Union Finance Minister.

- Inverted Duty Structure: Situation where tax on inputs > tax on final product, discouraging domestic value addition.

- Recent Decision (Sept 2025): GST Council revised rates across multiple sectors → auto, insurance, appliances, pharma, renewable energy, but also imposed higher rates in textiles, airlines, and services.

Relevance: GS III (Economy – Taxation, GST reforms, federal fiscal relations, sectoral impacts on industry and labour).

Key Changes

- Positive for Industry:

- Auto sector: Rate rationalisation + removal of GST Compensation Cess on certain vehicles.

- Pharma & Fertilisers: Corrected inverted duty structure → reduces input cost burden.

- Renewable energy: Adjustments encouraging investment in green projects.

- Consumer appliances: Lower duties on select items → boost demand.

- Negative for Some Sectors:

- Textiles & Garments: GST on labour charges raised 12% → 18% → affects small units, handlooms, embroidery, wedding wear.

- Cloth Manufacturers Association of India: Warned higher costs will hurt migrant workers and common consumers (woollens, handlooms, traditional clothing).

- Airlines: Criticised higher GST on non-economy class tickets.

- Service providers/SMEs: Fear higher compliance costs.

- Stock Market Reaction: Initial optimism but ended flat, Sensex barely up → reflects mixed industry sentiment.

Implications

- Economic Impact

- Rationalisation reduces litigation & compliance disputes.

- Correction of inverted duty structure supports Make in India and boosts domestic value chains.

- But labour-intensive textile sector hit → job losses possible for migrant/daily-wage workers.

- Social Impact

- Higher tax on garments affects low-income consumers → affordability issue.

- Migrant workers in textile hubs (Surat, Tiruppur, Panipat) likely to face wage squeeze.

- Political Angle

- Rate hikes on essential clothing → politically sensitive before elections, esp. in states with large textile workforce.

- Industries lobbying for rollback may pressure govt.

- Governance Angle

- Shows federal cooperation in GST Council but also trade-offs → boosting revenue vs protecting vulnerable industries.

- Addresses long-pending duty inversion, improving tax efficiency.

- Sectoral Winners & Losers

- Winners: Auto, pharma, renewable energy, fertilizers.

- Losers: Textiles, airlines, MSME service providers.

Should commercial speech on digital platforms be regulated?

Basics

- Commercial Speech: Expression with an economic motive (advertisements, influencer content, monetized performances). Recognised under Article 19(1)(a) (Tata Press Ltd. v. MTNL, 1995).

- Regulatory Context:

- IT Act, 2000 & BNS, 2023 provide mechanisms for prosecution and content removal.

- SC’s 25 Aug 2024 Order: Urged govt. to draft guidelines for social media content, triggered by derogatory remarks by comedians against persons with disabilities.

- Constitutional Framework:

- Free speech subject to reasonable restrictions under Article 19(2) (security, public order, decency, morality, etc.).

- Individual dignity is not an explicit ground under Art. 19(2), but SC upheld criminal defamation (2016) recognising dignity as linked to reputation.

Relevance: GS II (Polity – Fundamental Rights: Free Speech & Reasonable Restrictions; IT laws; Judiciary–Executive balance).

Arguments Against New Regulation

- Existing Laws Already Cover It: FIRs filed under BNS & IT Act show enforceability. Section 69A already provides takedown powers.

- Risk of Overreach: Using “dignity” as an independent ground risks expansive censorship.

- Chilling Effect: Comedians, satirists, journalists may self-censor, harming democratic debate.

- Judicial Precedent: SC has protected unpalatable speech (e.g., quashing FIR against Imran Pratapgadhi’s poem, 2024).

- Commercial Nature ≠ Justification for Regulation: Profit-driven speech still falls under free expression (Sakal Papers v. Union, 1962).

Arguments for Some Regulation

- Protection of Vulnerable Groups: Content mocking disabilities or minorities affects dignity and participation in public life.

- Social Responsibility: Commercialisation of free speech (influencer marketing, stand-up comedy, monetised social media) increases its reach and impact.

- Judicial Role of “Complete Justice”: SC has inherent jurisdiction to balance free expression with social harm.

- Safeguards Against Hate Speech: Commercial platforms amplify hate speech faster; some oversight is needed to prevent real harm.

Key Constitutional & Legal Precedents

- Sakal Papers v. Union (1962): Struck down govt. attempt to regulate newspaper page limit; reinforced commercial speech as part of free expression.

- Tata Press Ltd. v. MTNL (1995): Affirmed advertisements as part of free speech under Art. 19(1)(a).

- Subramanian Swamy v. Union of India (2016): Upheld criminal defamation, linking dignity with reputation.

- Recent SC orders:

- Protected “disturbing or offensive” speech (2024).

- Questioned excessive executive censorship via IT Act Sec. 69A.

Risks of Over-Regulation

- Censorship Creep: Govts may regulate under “social value” standards, suppressing dissent.

- Opaque Mechanisms: Existing takedown regime already lacks transparency and notice to content creators.

- Institutional Overreach: SC asking executive to draft regulations may reinforce state censorship with judicial backing.

Way Forward – Safeguards Needed

- Strong Review Mechanisms: Independent tribunals or oversight bodies for content removal.

- Clear Definitions: Avoid vague terms like “dignity” or “offensive content”.

- Stakeholder Consultation: Must include creators, civil society, and vulnerable groups—not just state or industry bodies.

- Transparency: Public disclosure of takedown/blocking orders; notice to affected parties.

- Balance Approach: Protect vulnerable groups from targeted ridicule while preserving space for satire, dissent, and artistic freedom.

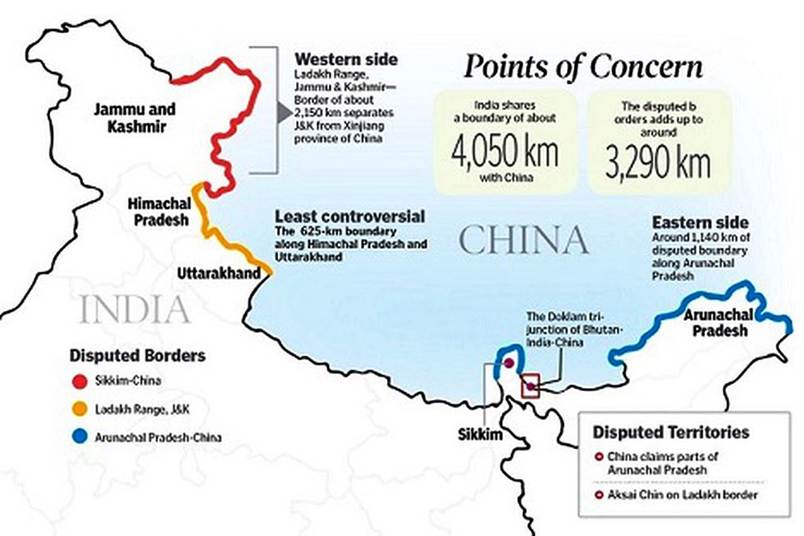

India-China: the making of a border

Basics of the Border Issue

- Colonial Legacy: Border derived from British (India) and Manchu (China) empires, drawn imprecisely in Himalayan, uninhabited terrain.

- Post-Independence Indian Position: India assumed British-era maps were final; avoided negotiations. China viewed border as undefined.

- Key Disputed Areas:

- Western Sector: Aksai Chin (strategically important for China’s Xinjiang–Tibet highway).

- Eastern Sector: Arunachal Pradesh (esp. Tawang), based on McMahon Line (1914 Simla Agreement with Tibet).

Relevance: GS I (History – Colonial Legacies) + GS II (IR – India-China Relations, Border Disputes) + GS III (Security – Border Management).

Beginning of Conflict

- China built Aksai Chin highway (1950s) → India discovered only later.

- 1959 Proposal: China suggested Line of Actual Control (LAC) + mutual pullback (20 km).

- 1960 Zhou Enlai Proposal: Swap deal (Aksai Chin to China, Arunachal to India). India rejected.

- 1962 War: Triggered by Indian forward moves in Aksai Chin; China retained Aksai Chin but withdrew in east north of McMahon Line.

Post-War Developments (1962–1979)

- 1967: Nathu La & Cho La clashes in Sikkim → Indian Army showed stronger resolve.

- 1975: Sikkim merged with India → Chinese protests.

- 1975: Formation of China Study Group (CSG) → institutionalized patrolling, mapping with satellite imagery.

- 1979: FM Vajpayee visited Beijing → first high-level political contact post-war; partial normalisation attempt.

1980s Escalation & Diplomacy

- 1980 Deng Proposal: China willing to accept McMahon Line if India recognised Aksai Chin status quo. India refused.

- 1981–85 Talks: Resumed but deadlocked; India wanted sector-by-sector talks, China insisted on package deal.

- 1983–86 Crisis:

- China demanded Tawang, shifting stance (linked to Tibet policy).

- 1986: Wangdung standoff → India launched Operation Falcon, strong forward deployment. Showed India’s improved military preparedness.

- 1988 Rajiv Gandhi Visit: Turning point in ties. Both sides agreed on “mutual understanding & mutual accommodation” (MUMA). Normalisation of ties + creation of Joint Working Group (JWG) on border issue.

Implications

- Strategic Factors:

- China needed Aksai Chin for Tibet–Xinjiang connectivity.

- India viewed Arunachal (esp. Tawang) as non-negotiable due to cultural, historical, and security reasons.

- Diplomatic Approaches:

- China repeatedly offered “package deals”; India preferred incremental, sectoral talks.

- India’s stance shaped by 1962 trauma → reluctance to accept territorial concessions.

- Military Evolution:

- 1962: Indian Army unprepared → humiliation.

- Post-1967 & 1986: India demonstrated stronger capability & resolve.

- Geopolitical Context:

- 1960s–70s: China wary of Soviet Union, sought neutralising India.

- 1980s: China recalibrated post-Afghanistan war, wary of Indo-US proximity, opened to India.

- Outcome by late 1980s:

- Border dispute unresolved.

- Shift from confrontation to “peaceful coexistence + negotiation”.

- Framework for future CBMs (Confidence Building Measures) laid.

‘India’s birth rate down, first dip in TFR in 2 years’

Basics

- Crude Birth Rate (CBR): No. of live births per 1,000 population/year.

- Declined from 19.1 (2022) → 18.4 (2023).

- Total Fertility Rate (TFR): Avg. no. of children a woman is expected to bear during her reproductive span.

- Declined from 2.0 (2021 & 2022) → 1.9 (2023).

- First dip in 2 years.

- Replacement-level fertility: 2.1 (needed for population stabilization).

- Highest CBR (2023): Bihar (25.8).

- Lowest CBR (2023): Tamil Nadu (12).

- Highest TFR: Bihar (2.8).

- Lowest TFR: Delhi (1.2).

- States with TFR above replacement level: Northern India – Bihar (2.8), UP (2.6), MP (2.4), Rajasthan (2.3), Chhattisgarh (2.2).

- States/UTs with lowest TFRs: Delhi (1.2), West Bengal (1.3), Tamil Nadu (1.3), Maharashtra (1.4).

- Elderly proportion (2023): 9.7% of population (↑ 0.7% in one year).

- Highest elderly share: Kerala (15%).

- Lowest: Assam, Jharkhand (7.6%), Delhi (7.7%).

Relevance: GS I (Society – Demographic Trends, Population Issues) + GS II (Governance – Health, Education, Social Policy).

Demographic Trends

- India’s fertility is steadily declining → convergence towards below-replacement fertility in majority of states (18 States/UTs).

- North-South divide:

- North/Central India still above replacement (Bihar, UP, MP, Rajasthan).

- South & urbanised states far below replacement (TN, WB, Delhi, Maharashtra).

- Indicates demographic heterogeneity – “two Indias” in population dynamics.

Implications of Falling TFR

- Population Stabilisation: India nearing replacement level fertility; long-term population expected to peak around mid-2060s.

- Ageing Society: Elderly share rising (9.7% in 2023; Kerala already at 15%).

- Labour Force Impact: Declining fertility may affect working-age population growth after 2040, impacting economic growth potential.

- Gender Dimension: Falling fertility often linked with female education, urbanisation, workforce participation, and healthcare access.

Policy & Governance Aspects

- Civil Registration System (CRS) & SRS: Key demographic data sources; delays (4-year lag in CRS, MCCD) weaken timely policymaking.

- Healthcare Planning: Rising elderly population requires stronger geriatric care, social security, and pensions.

- Regional Planning: High fertility states (Bihar, UP, MP) will continue to add to India’s population momentum → implications for resource allocation, jobs, and migration.

- Population Policies: Need state-specific approaches rather than “one-size-fits-all.”

Socio-Economic Drivers of Fertility Decline

- Education & Awareness: Female literacy rise → lower fertility.

- Urbanisation: Higher in low-TFR states (Delhi, TN, WB).

- Access to Family Planning: More widespread in southern/western states.

- Economic Aspiration: Shift from “quantity to quality” of children (health, education).

- Delayed Marriage & Fertility Choices: Seen in urban India.

Challenges & Opportunities

- Opportunities:

- Fertility decline supports sustainable development.

- Lower dependency ratio in short term (demographic dividend).

- Challenges:

- Demographic imbalance between north (population boom) and south (population stagnation/decline).

- Ageing burden → healthcare, pensions, social support.

- Skewed sex ratio and declining fertility may exacerbate social issues.

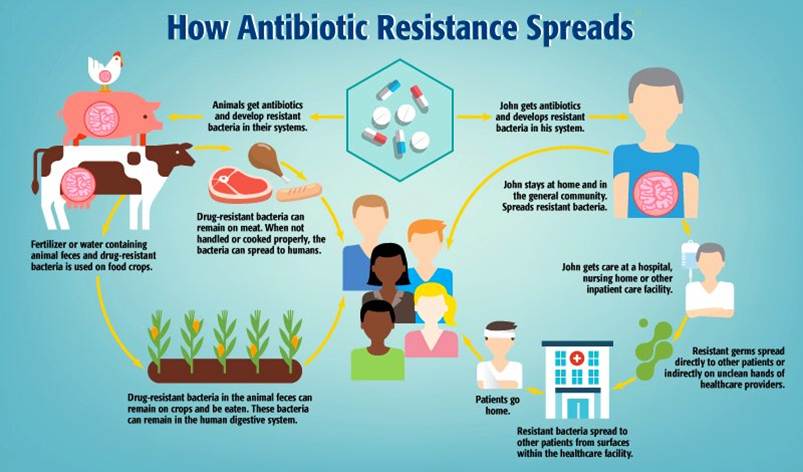

How the antibiotic culture in India imperils mental health

Basics

- Context: Rising mental health awareness in India, but antibiotic misuse poses hidden risks via gut-brain axis disruption.

- Gut-brain axis: Bidirectional communication between gastrointestinal tract and brain, influencing mood, cognition, and stress.

- Antibiotics’ role: Overuse disturbs gut microbiota → contributes to anxiety, depression, cognitive decline.

- India’s antibiotic crisis:

- 2,67,000 deaths due to AMR (2021); projected 1.2 million by 2030 (IHME).

- ~50% antibiotics consumed in India are unapproved formulations (Lancet 2022).

- Institutions involved: NIMHANS, AIIMS exploring gut dysbiosis–psychiatric disorder links.

Relevance: GS II (Health – Public Health & Policy) + GS III (Science & Tech – Antibiotic Resistance, Gut-Brain Axis Research).

Health & Science Dimensions

- Gut microbiota produces serotonin, dopamine, and SCFAs (short-chain fatty acids) → regulate mood, sleep, stress.

- Antibiotic misuse → gut dysbiosis → inflammation (IL-6, TNF-α), neurochemical imbalance, cognitive decline.

- Psychobiotics (probiotics + prebiotics) emerging as adjunct therapy for depression and anxiety.

- Probiotic-rich Indian foods (curd, idli, dosa, pickles) naturally support microbial diversity.

Mental Health Impact

- Gut disruption linked to anxiety, depression, and neurodegenerative disorders.

- Dysbiosis-induced inflammation alters neurotransmitter metabolism and neuroplasticity.

- Psychiatric care must integrate gastrointestinal and nutritional assessments.

Drivers of Antibiotic Misuse in India

- Cultural: Preference for “quick fixes” over lifestyle changes.

- Systemic: Over-the-counter sales, weak enforcement of prescription laws.

- Economic: Doctors over-prescribe to satisfy patients; pharmacies act as dispensaries.

- Rural-urban gap: Easy availability in rural/semi-urban areas without medical oversight.

Governance & Policy Challenges

- Weak enforcement of CDSCO prescription rules.

- Inadequate awareness campaigns on antibiotic misuse.

- Need for stronger AMR surveillance networks (INSAR expansion with mental health metrics).

- Public health campaigns (NHM, Ayushman Bharat) yet to integrate gut-brain literacy.

Solutions & Way Forward

- Regulatory: Strict prescription-only antibiotic sales, penalties for violations.

- Public Health: Awareness drives on gut health, microbiome, and mental well-being.

- Medical Education: Antibiotic stewardship integrated into medical curriculum.

- Research & Data: Invest in Indian microbiome research; link AMR + mental health surveillance.

- Integrated Care: Combine psychiatry, gastroenterology, nutrition, and public health.

- Traditional Knowledge: Promote fermented foods as natural probiotics.

Logs in Himachal floodwaters, SC response

Basics

- Context: Supreme Court (SC) took suo motu note of videos showing timber logs washed away in Himachal floods.

- Prima facie concern: Possible case of illegal felling of trees in Himalayan states.

- Bench: Chief Justice DY Chandrachud and Justice BR Gavai.

- Parties involved: Centre, NDMA, MoEFCC, Jal Shakti Ministry, NHAI, States (HP, Uttarakhand, Punjab, J&K).

- Deadline: 2 weeks to respond.

Relevance: GS I (Geography – Himalayan Ecology) + GS II (Polity – Judicial Intervention, Environmental Governance) + GS III (Disaster Management).

Key Issues Highlighted

- Flood-linked destruction: Logs floating downstream → linked to landslides, deforestation.

- Ecological damage: Loss of forest cover → destabilises slopes, worsens floods.

- Illegal logging nexus: Timber mafia suspected behind large-scale tree felling.

- Infrastructure vulnerability:

- Example: 14 tunnels between Chandigarh–Manali face landslide risks.

- “Near-death trap” situation during blockages; 300 people stranded on one occasion.

- Development vs Ecology: CJI observed – “Development has to be there, but must balance with ecology.”

Petitioner’s Concerns

- Call for national-level plan: Mechanism for disaster prevention & eco-protection in Himalayan states.

- Eco-fragility: Frequent cloudbursts, flash floods, landslides intensifying due to unchecked deforestation, road cutting, dam projects.

- Pristine ecology threat: Himalayan biodiversity and rivers at stake.

SC Observations

- Unprecedented landslides and floods in HP, Uttarakhand, Punjab.

- Videos show timber logs in floodwaters → indicates systemic illegal felling.

- Urged immediate response from officials to prevent future ecological collapse.

Overview

- Environmental Angle:

- Deforestation weakens slope stability → landslides and flash floods.

- Floating logs = dual disaster (physical obstruction + ecological loss).

- Fragile Himalayan ecosystem cannot sustain large-scale construction + deforestation.

- Governance & Policy Issues:

- Weak enforcement of Forest Conservation Act, 1980 & Indian Forest Act, 1927.

- Poor coordination between state forest departments and NHAI during road expansion.

- Need for stricter timber tracking, community monitoring, and green clearances.

- Disaster Management Angle:

- NDMA and states lack real-time flood and landslide monitoring.

- Rescue challenges in tunnels/remote highways highlight poor contingency planning.

- Ecosystem-based disaster risk reduction (Eco-DRR) largely missing.

- Socio-economic Angle:

- Local livelihoods disrupted (farmers, transporters, small traders).

- Increased vulnerability of downstream communities (Punjab flood plains).

- Hidden costs of “development-at-all-costs” approach.

- Way Forward:

- Independent probe into illegal logging in Himalayas.

- Strict forest clearance norms for infrastructure.

- Eco-sensitive zone expansion + carrying capacity studies.

- Investment in early warning systems, slope stabilisation, tunnel safety.

- Promotion of community-led forest monitoring & afforestation.

New Foreigners Act, 2025

Basics

- Law: Immigration and Foreigners Act, 2025 (in force from Sept 1, 2025).

- Objective: Overhaul India’s framework on entry, stay, movement, and exit of foreigners.

- Consolidation: Merges 4 earlier Acts –

- Passport (Entry into India) Act, 1920

- Registration of Foreigners Act, 1939

- Foreigners Act, 1946

- Immigration (Carrier’s Liability) Act, 2000

- Need for change: Old laws = fragmented, colonial, ambiguous, poor enforcement.

Relevance: GS II (Polity – Migration, National Security, Citizenship & Foreigners Laws, Centre–State Powers).

Key Provisions & Analysis

- Documentation Rules:

- All foreigners must carry valid passport/visa; penalties for non-compliance.

- Defined immigration posts for legal entry/exit.

- Defined Registration & Monitoring:

- Mandatory registration with Foreigners Regional Registration Officers (FRROs).

- Hotels, transport, religious institutions, employers → must report foreign clients/workers.

- Special Permits:

- Required for restricted/prohibited areas (esp. border/tribal zones).

- Enforcement & Penalties:

- Powers of entry, search, arrest with due procedure.

- Fines from ₹10,000 to ₹5 lakh.

- Offences: overstaying, fake documents, illegal entry, visa misuse.

- Delegation & Centralisation:

- Central government retains core powers; can delegate to states.

- Emergency provisions for quick directions.

- Exemptions & Categories:

- Special rules for Tibetans, Sri Lankan Tamils, Bhutanese/Nepalese citizens, minorities from Pakistan–Afghanistan–Bangladesh.

- Limited protection for bona fide mistakes.

- Different fine slabs (e.g., Tibetan/Bhutanese migrants, Rohingya, Buddhist monks).

- New in the statute:

- Digital records: compulsory reporting by hotels, universities, hospitals.

- Diplomatic clauses: rules for warships, foreign military, diplomats.

- Exemption categories: tighter listing for humanitarian cases, minorities, Tibetans, Sri Lankans.

Likely Impact

- Positive:

- Single law → clarity & consistency.

- Stronger enforcement & digital monitoring.

- Better national security management.

- Concerns:

- Risk of over-centralisation.

- Compliance burden on institutions (hotels, universities).

- Possible misuse against vulnerable groups (e.g., refugees).

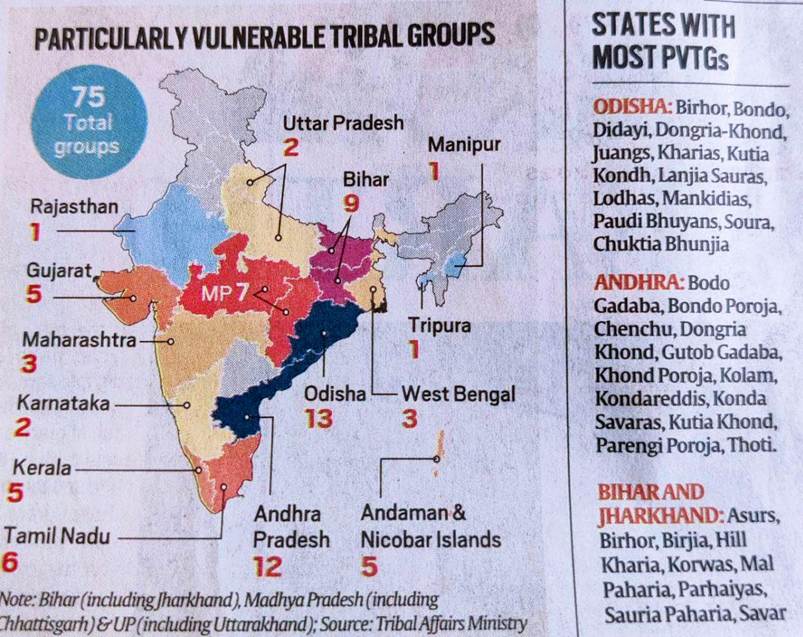

PVTGs (Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups) and Enumeration Issues

Basics

- PVTGs: Sub-category within Scheduled Tribes (STs), identified as the most vulnerable.

- Origin of Concept: Based on the Dhebar Commission (1960–61) which noted disparities among tribal groups → recommended identification of “Primitive Tribal Groups” (renamed as PVTGs in 2006).

- Criteria for Identification:

- Declining/stagnant population

- Low literacy

- Pre-agricultural level of technology (hunting, gathering, shifting cultivation)

- Economic backwardness

- Geographical and social isolation

Relevance: GS II (Polity – Migration, National Security, Citizenship & Foreigners Laws, Centre–State Powers).

Overview

Historical Context

- 1975: Govt identified 52 tribal groups as PVTGs.

- 1993: 23 more added → total 75 PVTGs.

- Spread across 18 States + 1 UT (A&N Islands).

Enumeration Issues

- So far, PVTGs never separately enumerated in Census (treated under STs).

- Govt now wants separate data on PVTGs for targeted schemes like Pradhan Mantri Janjati Adivasi Nyaya Maha Abhiyan (PM-JANMAN).

- Challenge: Lists of STs (and PVTGs) are state-specific, not uniform nationally.

Past Efforts

- Census 2011: Some PVTGs (Baigas in MP, Abujh Marias in Chhattisgarh, Kamars) enumerated separately, but not uniform.

- 2013: Abujh Marias + Hill Korbas in Chhattisgarh included in ST list by Parliament law.

- 2016 Lok Sabha Reply: 75 PVTGs officially recognized (40 listed as “single-entry” groups under Article 342).

Current Situation

- As per 2011 Census, 13 PVTGs were listed under single-entry STs.

- Examples: Great Andamanese, Onges, Jarawas, Sentinelese (Andaman), Kutia Kondh, Birhor, Korwa, Sahariya etc.

- Population estimates (2011–13 survey):

- Total: 27.45 lakh PVTGs across India.

- Highest population: Madhya Pradesh (6.57 lakh).

- Lowest: Andaman & Nicobar tribes (few hundred) – e.g., Sentinelese (population ~50).

Policy Significance

- PM-JANMAN Scheme (2023): Rolled out to improve housing, health, education, livelihood support, and basic amenities in 200+ districts.

- Enumeration critical for:

- Addressing health gaps (maternal/child mortality, malnutrition, endemic diseases).

- Education & livelihoods (preserve skills, provide access).

- Infrastructure planning (housing, roads, connectivity).

- Monitoring inclusion in welfare schemes.

Challenges

- Identification Criteria outdated (still uses Dhebar Commission benchmarks).

- Social exclusion & isolation → remote forests, islands.

- Data Gaps → many still not fully counted, esp. uncontacted tribes like Sentinelese.

- State-specific lists complicate uniform national policy.

Larger Significance

- Ensuring inclusive development without eroding tribal autonomy & culture.

- Supports SDGs: poverty reduction, health, education, inequality.

- Strengthens tribal justice framework under Constitution (Art. 46, 275, 342).