Published on Jan 17, 2026

Daily Current Affairs

Current Affairs 17 January 2026

Content

- Startup India @10 — Highest Annual Spike in Start-up Registrations

- Expert Panel Sets Norms for Religious Structures in Wildlife Sanctuaries

- Nobel Prize Debate — Politicisation and Symbolism of the Nobel Peace Prize

- Kaziranga Elevated Corridor — Eco-Sensitive Infrastructure to Reduce Wildlife Mortality

- Land Is Power — Women’s Land Rights and Agrarian Gender Inequality in India

- Drowning in Its Home — Sangai (Dancing Deer) and the Collapse of Floating Wetlands

Startup India @10 — Highest Annual Spike in Start-up

Why in News ?

- Prime Minister Narendra Modi stated that ~44,000 start-ups were registered in 2025, the highest annual addition since the launch of Startup India.

- Statement made during the 10th anniversary of the Startup India Mission.

- India now positioned as the 3rd largest start-up ecosystem globally.

Relevance

GS II – Governance

- Government policies for entrepreneurship promotion.

- Role of DPIIT, regulatory reforms, ease of doing business.

- Centre–State competition in start-up ecosystems.

GS III – Economy

- Start-ups as drivers of:

- Job creation.

- Innovation-led growth.

- Capital market deepening (IPOs).

- MSME–start-up linkage in value chains.

- Shift from factor-led to innovation-led growth.

Startup India: Core Basics

- Launch date: 16 January 2016.

- Nodal Ministry: Ministry of Commerce & Industry (DPIIT).

- Core objectives:

- Foster innovation.

- Promote entrepreneurship.

- Enable investment-led growth.

- Key instruments:

- Start-up recognition by DPIIT.

- Fund of Funds for Start-ups (FFS).

- Tax exemptions & compliance easing.

Key Data & Evidence

- 2025:

- ~44,000 new start-ups registered (highest single-year jump).

- Ecosystem position:

- India = 3rd largest globally (after US & China).

- Trend highlighted:

- Start-ups → Unicorns → IPOs → Job creation.

- Registration ≠ success; but reflects pipeline depth.

Economic Dimension

- Growth engine:

- Start-ups driving:

- Job creation.

- Capital formation.

- Productivity gains.

- Start-ups driving:

- Structural shift:

- From factor-led growth → innovation-led growth.

- Capital markets linkage:

- Rising start-up IPOs deepen domestic capital markets.

- MSME–Start-up continuum:

- Start-ups complement MSMEs in value chains.

Governance & Administrative Dimension

- Regulatory reforms:

- Self-certification under labour & environmental laws.

- Faster incorporation & IPR facilitation.

- Digital public infrastructure:

- Aadhaar, UPI, ONDC enabling low-cost scaling.

- Centre–State role:

- States competing via start-up policies, incubators.

Social Dimension

- Democratisation of entrepreneurship:

- Growth beyond metros into Tier-2/Tier-3 cities.

- Youth dividend utilisation:

- Converts job-seekers into job-creators.

- Women entrepreneurship:

- Rising share, but still underrepresented in funding.

Technology & Innovation Dimension

- Strong presence in:

- FinTech, EdTech, HealthTech, SaaS, Climate-tech.

- Leveraging:

- AI, data analytics, digital platforms.

- Start-ups as drivers of:

- Indigenous innovation.

- Atmanirbhar Bharat goals.

Challenges

- Quality vs quantity:

- High registrations, but survival rates vary.

- Funding concentration:

- Venture capital skewed towards few sectors & cities.

- Regulatory uncertainty:

- Taxation (angel tax legacy issues).

- Compliance burden for scaling firms.

- Job quality concerns:

- Informal, gig-based employment dominance.

Way Forward

- Next phase: Startup India 2.0

- Focus on deep-tech & manufacturing start-ups.

- Credit diversification

- Beyond VC: development finance, patient capital.

- Inclusive entrepreneurship

- Women, SC/ST, rural & agri-start-ups.

- Outcome-based support

- Survival, scale, exports—not just registrations.

- Regulatory predictability

- Stable tax & compliance regime for scale-ups.

Prelims Pointers

- Startup India launched in 2016, not post-COVID.

- DPIIT recognises start-ups (not NITI Aayog).

- Fund of Funds ≠ direct equity funding.

- Unicorn = private firm valued at $1 billion+.

Expert Panel Sets Norms for Religious Structures in Wildlife Sanctuaries

Why in News ?

- The Standing Committee of the National Board for Wildlife (SCNBWL) has framed guidelines on diversion/regularisation of forest land for religious structures inside Protected Areas (PAs).

- Triggered by the Balaram–Ambaji Wildlife Sanctuary (Gujarat) case, where diversion of forest land for temples was proposed and later revoked.

- Raises critical issues of encroachment vs faith, forest rights settlement, and precedent-setting in wildlife governance.

Relevance

GS II – Polity & Governance

- Balance between Fundamental Rights (Article 25) and DPSPs (Article 48A).

- Role of statutory bodies: NBWL / SCNBWL.

- Rule-based governance vs discretionary clearances.

GS III – Environment & Biodiversity

- Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972.

- Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980.

- Protected Areas governance and encroachment control.

Background & Case Context

- Balaram–Ambaji Wildlife Sanctuary hosts two temples claimed to be “historical”.

- July 2024: SCNBWL initially cleared 0.35 ha forest land use for a religious trust.

- October 2024: Clearance revoked after it was found that:

- Rights of the Trust were not recorded in forest settlement records.

- December 2025: Draft normative guidelines presented to SCNBWL to avoid ad-hoc decisions in future.

Core Guidelines

- General Principle:

- Any construction or expansion on forest land after 1980 = encroachment.

- Exceptional Window:

- Only if:

- State issues a reasoned, documented order, and

- Justifies regularisation on exceptional grounds.

- Such cases to be referred to the Environment Ministry for case-by-case scrutiny.

- Only if:

- Key cut-off year: 1980 (linked to Forest (Conservation) Act).

Constitutional & Legal Dimension

- Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980:

- Central approval mandatory for diversion of forest land.

- Post-1980 non-forestry use is presumptively illegal.

- Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972:

- Strong protection regime for National Parks & Sanctuaries.

- Infrastructure allowed only if non-detrimental to wildlife.

- Article 25 (Freedom of Religion):

- Subject to public order, morality, health, and other fundamental rights.

- Does not override environmental laws.

- Article 48A & 51A(g):

- State and citizen duty to protect environment and wildlife.

Governance & Administrative Dimension

- Problem exposed:

- Many sanctuaries still have unsettled forest rights and claims.

- Poor-quality forest settlement records create ambiguity.

- Risk of precedent:

- Regularising one religious structure may open floodgates across PAs.

- Institutional response:

- Shift from case-by-case discretion → rule-based SOP.

- Role of SCNBWL:

- Apex technical-cum-policy filter to balance conservation vs development/faith.

Social & Ethical Dimension

- Faith vs Ecology dilemma:

- Religious sentiments are socially powerful but ecologically footprint-heavy.

- Ethical concern:

- Selective accommodation of religion risks normalising encroachment.

- Equity issue:

- If faith-based claims allowed, why deny other community or livelihood claims?

Environmental & Wildlife Dimension

- Protected Areas are:

- Inviolate cores for biodiversity.

- Highly sensitive to fragmentation, noise, footfall, waste.

- Religious infrastructure often leads to:

- Roads, shops, accommodation, pilgrim influx → secondary impacts.

- Guidelines aim to:

- Prevent “incremental degradation” of sanctuaries.

Challenges

- Implementation gap:

- States may still push proposals citing “historical existence”.

- Data deficiency:

- Lack of authentic records on pre-1980 structures.

- Political pressure:

- Religious institutions have high mobilisation capacity.

- Forest Rights Act overlap:

- Unsettled FRA claims complicate decision-making.

Way Forward

- Strict adherence to 1980 cut-off as non-negotiable baseline.

- Time-bound settlement of forest rights under FRA before considering any diversion.

- Independent ecological impact assessment even for “small” religious uses.

- No new construction principle:

- Only maintenance of genuinely pre-1980, legally recorded structures.

- National SOP:

- Uniform criteria to avoid State-level arbitrariness.

- Public communication:

- Clarify that conservation is not anti-faith, but pro-intergenerational equity.

Prelims Pointers

- SCNBWL ≠ NBWL (NBWL is chaired by PM; SCNBWL handles clearances).

- Forest (Conservation) Act operative year: 1980.

- Post-1980 forest constructions = encroachments (default rule).

- Religious freedom is not absolute.

Nobel Prize with Special Focus on the Nobel Peace Prize

Why is it in News?

- María Corina Machado publicly presented her Nobel Peace Prize medal to Donald Trump during a recent meeting in the US.

- The act was described as a symbolic gesture of gratitude for Trump’s past support to Venezuela’s opposition and democratic cause.

- This has triggered debate because:

- Nobel medals are personal property of laureates and can legally be gifted or sold under the statutes of the Norwegian Nobel Committee.

- However, transferring a Peace Prize medal to a political leader raises questions about politicisation of the Nobel Peace Prize.

- The episode has revived wider discussion on:

- Whether the Nobel Peace Prize is being used as a political signal rather than a purely humanitarian recognition.

- The distinction between symbolic diplomacy vs institutional neutrality of global awards.

Relevance

GS Paper I – World History / Society

- Global institutions and moral authority.

- Evolution of international recognition systems.

GS Paper II – International Relations

- Soft power and norm-setting in global politics.

- Awards as instruments of diplomatic signalling.

- Institutional neutrality vs political messaging.

Nobel Prize: Core Basics

- Instituted by the will of Alfred Nobel (1895).

- First awarded: 1901.

- Original categories:

- Physics

- Chemistry

- Physiology/Medicine

- Literature

- Peace

- Economics added later (1968) → Not part of original Nobel will.

Nobel Peace Prize: Unique Institutional Design

- Awarded by Norwegian Nobel Committee.

- Ceremony held in Oslo, not Stockholm.

- Rationale:

- Norway–Sweden union context at the time of Nobel’s will.

- Unlike other Nobel Prizes:

- Awarded to individuals or organisations.

- Can be given for political processes, activism, conflict resolution, humanitarian work.

Eligibility, Nomination & Decision Process

- Who can nominate?

- National parliamentarians, ministers.

- University professors (relevant fields).

- Previous laureates.

- International courts & organisations.

- Key point:

- Nomination ≠ endorsement.

- Hundreds nominated annually; only one laureate selected.

- Deliberations are confidential for 50 years.

Ownership of the Nobel Medal

- Nobel medal, diploma, and prize money:

- Become personal property of the laureate.

- Nobel statutes:

- Do not prohibit selling, donating, or auctioning medals.

- Important examples:

- Dmitry Muratov:

- Auctioned Peace Prize medal (2022).

- Proceeds (~USD 103.5 million) donated for Ukrainian children affected by war.

- Carlos Saavedra Lamas:

- Medal sold in 2014.

- Dmitry Muratov:

- Insight:

- Moral authority lies in use of prize, not physical possession.

Political Dimension of the Nobel Peace Prize

- Peace Prize often reflects contemporary global conflicts and moral priorities.

- Frequently criticised for:

- Western normative bias.

- Awarding aspirational peace rather than achieved peace.

- Examples often debated in UPSC interviews:

- Awards during ongoing conflicts.

- Recognition of political opposition figures.

- However:

- Nobel Committee defends Peace Prize as a norm-setting instrument, not merely retrospective reward.

International Relations Dimension

- Peace Prize as:

- Soft power instrument.

- Moral signalling mechanism in global politics.

- Can:

- Legitimize political movements.

- Increase diplomatic pressure on regimes.

- Sometimes causes:

- Diplomatic discomfort.

- Accusations of interference in domestic affairs.

Economic & Institutional Aspect

- Prize money:

- Approx. 10 million Swedish Krona (value may vary annually).

- Nobel Foundation:

- Manages endowment.

- Prize money independent of medal ownership.

Challenges

- Politicisation

- Perception of ideological selectivity.

- Premature awards

- Given before outcomes are secured.

- Eurocentric norms

- Global South under-representation historically.

- Symbol vs substance

- Media focus on personalities rather than peace outcomes.

Way Forward

- Greater transparency post 50-year disclosure.

- Broader inclusion of:

- Grassroots peacebuilders.

- Community-level conflict resolution.

- Balanced recognition:

- Combine moral courage with demonstrable outcomes.

- Reinforce Peace Prize as:

- Instrument of conscience, not geopolitics.

Prelims Pointers

- Peace Prize awarded in Norway, others in Sweden.

- Economics Prize ≠ original Nobel category.

- Medal ownership lies with laureate.

- Nobel deliberations sealed for 50 years.

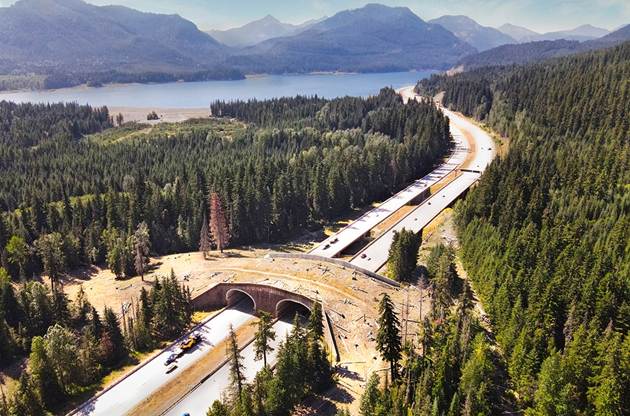

Kaziranga Elevated Corridor — Curbing Wildlife Mortality through Eco-Sensitive Infrastructure

Why in News ?

- Prime Minister laid the foundation stone of a 34.5-km elevated corridor along/through Kaziranga National Park.

- Objective: Reduce animal deaths caused by heavy traffic on NH-715 (formerly NH-37), especially during Brahmaputra floods.

Relevance

GS III – Environment

- Human–wildlife conflict mitigation.

- Wildlife corridors and ecological connectivity.

- Conservation in flood-prone ecosystems.

GS III – Infrastructure

- Sustainable infrastructure.

- Disaster-resilient transport planning.

- Integrating ecology into highway design.

Project Snapshot

- Length: 34.5 km (elevated corridor).

- Cost: ~₹6,950 crore.

- Route: NH-715 connecting Kaziranga–Eastern Assam–Guwahati.

- Ecological linkage:

- Kaziranga floodplains ↔ Karbi Anglong hills.

- Complementary works:

- Widening of 30.22 km existing roads.

- 2 km long flyovers near Bokakhat & Jakhalabandha.

Ecological & Environmental Dimension

- Flood-driven migration:

- Annual Brahmaputra floods submerge low-lying grasslands.

- Wildlife (rhinos, elephants, deer, predators) migrate to higher grounds of Karbi Anglong plateau.

- Barrier effect of highways:

- NH-715 cuts across natural corridors.

- High vehicle speed = major mortality driver.

- Scientific evidence:

- Wildlife Institute of India study:

- 2016–17: 63 animals killed on NH-715 in one year.

- Included apex predator (Indian leopard).

- Wildlife Institute of India study:

- Elevated corridor benefit:

- Restores horizontal ecological connectivity.

- Minimises surface-level human–wildlife interaction.

Governance & Administrative Dimension

- Shift in infrastructure paradigm:

- From “road through forest” → “road over wildlife landscape”.

- Inter-agency coordination:

- MoRTH + Assam Govt + Forest Dept + WII inputs.

- Eco-sensitive zone (ESZ) logic:

- Corridor aligns with ESZ norms without halting development.

- Challenge:

- Construction-phase disturbance in a sensitive zone.

Economic Dimension

- Trade-off resolution:

- Maintains Assam’s key arterial connectivity to Guwahati.

- Avoids economic losses from:

- Traffic disruptions during floods.

- Wildlife-vehicle collisions.

- Cost-effectiveness:

- High upfront cost but long-term savings in:

- Wildlife loss.

- Accident compensation.

- Road maintenance due to flood damage.

- High upfront cost but long-term savings in:

Social & Ethical Dimension

- Ethics of coexistence:

- Acknowledges wildlife movement as a right, not a nuisance.

- Local livelihoods:

- Reduced road closures benefit tourism & transport workers.

- Cultural value:

- Kaziranga symbolises India’s conservation ethic (one-horned rhino).

Security & Strategic Dimension

- NH-715 is a strategic connectivity route in eastern Assam.

- Ensures:

- All-weather movement.

- Disaster-resilient infrastructure in flood-prone terrain.

Challenges

- Construction impacts:

- Noise, vibration, light pollution.

- Speed management:

- Elevated roads can encourage overspeeding if not regulated.

- Habitat compression risk:

- If feeder roads & urbanisation expand unchecked.

- Monitoring gap:

- Need for post-construction ecological audits.

Way Forward

- Design & engineering

- Wildlife-friendly pillars spacing.

- Natural vegetation underpasses.

- Traffic regulation

- Strict speed limits.

- AI-enabled animal detection & warning systems.

- Construction safeguards

- Seasonal work restrictions during peak migration.

- Noise & light mitigation protocols.

- Replication

- Scale model to:

- Nilgiris–Bandipur.

- Pench–Kanha.

- Eastern Ghats corridors.

- Scale model to:

- Institutionalisation

- Make WII ecological clearance mandatory for highways in protected landscapes.

Prelims Pointers

- NH-715 (old NH-37) skirts Kaziranga NP.

- Kaziranga = UNESCO World Heritage Site.

- Karbi Anglong = key highland refuge during floods.

- Elevated corridors ≠ underpasses; both are wildlife mitigation tools.

Kaziranga National Park

- Location: Golaghat & Nagaon districts, Assam; south bank of the Brahmaputra River.

- Status:

- Declared National Park (1974).

- UNESCO World Heritage Site (1985).

- Tiger Reserve (2006) under Project Tiger.

- Global Significance:

- Hosts ~2/3rd of the world’s population of the One-horned Indian Rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis).

- Biodiversity Profile:

- “Big Five” of Kaziranga: Rhino, Tiger, Elephant, Wild Water Buffalo, Swamp Deer.

- High tiger density (among the highest globally).

Land is Power — Women’s Land Rights in India

Why in News ?

- Recent field-based reportage from Uttarakhand highlights feminisation of agriculture without feminisation of land ownership.

- Despite constitutional and legal reforms, women cultivators remain invisible in land records, excluding them from schemes like PM-KISAN Samman Nidhi.

- Reinforces long-standing academic evidence (Bina Agarwal) on land as the core determinant of women’s power, security, and autonomy.

Relevance

GS I – Indian Society

- Gender inequality in agrarian structures.

- Feminisation of agriculture.

GS II – Governance & Social Justice

- Implementation gaps in welfare schemes (PM-KISAN, KCC).

- Land as a State subject; federal challenges.

- Women empowerment through asset ownership.

Core Problem Statement

- Women do most agricultural work but do not own land → No legal farmer status → No scheme access → Economic disempowerment.

Constitutional & Legal Dimension

- Constitutional backing

- Article 14: Equality before law.

- Article 15(3): Affirmative action for women.

- Article 39(b), (c): Equitable distribution of material resources.

- Statutory framework

- Hindu Succession Act, 1956: First recognition of women’s inheritance.

- 2005 Amendment:

- Daughters = coparceners by birth (ancestral property incl. agricultural land).

- Applies irrespective of marital status.

- Key gap

- De jure equality ≠ de facto ownership.

- Land largely transferred to women only as widows, not as daughters.

Governance & Administrative Dimension

- Land records & farmer identity

- Ownership-based definition of “farmer” excludes women cultivators.

- Digitisation (DILRMP) replicates patriarchal ownership patterns.

- Scheme access failure

- PM-KISAN, KCC, crop insurance → land title mandatory.

- Result: Women submit affidavits instead of enjoying rights.

- Federal issue

- Land = State subject → uneven implementation across states.

Economic Dimension

- Productivity & credit

- No land title → no collateral → no formal credit.

- Zero/near-zero women Kisan Credit Cards in many hill districts.

- Macroeconomic loss

- FAO estimate (generic): Equal access to productive resources could raise farm output significantly.

- Migration link

- Male out-migration → women manage farms → “managerial feminisation without asset control.”

Social & Ethical Dimension

- Patriarchal norms

- Daughters “given away” at marriage → denied inheritance.

- Social pressure to relinquish legal share.

- Intra-household power

- Land ownership:

- Enhances bargaining power.

- Reduces domestic violence risk (Bina Agarwal’s findings).

- Land ownership:

- Intersectionality

- Dalit, Adivasi women face:

- Poor land quality.

- No demarcation, water, or extension support.

- Dalit, Adivasi women face:

Environmental & Sustainability Dimension

- Women land managers:

- Preserve forests, soil fertility, biodiversity.

- Promote mixed cropping, organic manure.

- Link to SDGs

- SDG 1 (No Poverty), SDG 5 (Gender Equality), SDG 15 (Life on Land).

Data & Evidence

- National Family Health Survey

- Women owning land alone:

- ~7% (2014–15) → ~8% (2019–21).

- Joint ownership:

- ~21% → ~23%.

- Women owning land alone:

- PM-KISAN (Rajya Sabha, Dec 2024):

- ~87 million beneficiaries.

- <20 million women (~2–3 out of 10).

- Uttarakhand: ~16% women beneficiaries.

- UN Women

- Even where women do >75% farm work, ownership remains male-dominated.

Challenges

- Implementation deficit

- Laws exist; enforcement weak.

- Institutional apathy

- Revenue officials resist joint/matrilineal titles.

- Awareness gap

- Women unaware of location/utility of allotted land.

- Design flaw

- Land titles without irrigation, extension, or market access = symbolic empowerment.

Way Forward

- Land record reforms

- Mandatory joint spousal titles in all government land transfers.

- Scheme redesign

- PM-KISAN, KCC eligibility based on cultivation + management, not just ownership.

- Administrative nudges

- Stamp duty rebates for women land registration (best practices from states).

- Institutional support

- Boundary demarcation, water access, extension services post-allotment.

- Normative change

- Panchayat-led awareness on daughters’ inheritance rights.

- Tribal areas

- Effective implementation of forest & community land rights with women as primary title holders.

Drowning in its Home — Sangai (Dancing Deer) & Collapse of Floating Wetlands

Why in News ?

- Recent ecological assessments warn that the Sangai (Dancing Deer) is approaching an extinction-level event due to collapse of floating meadows (phumdis) in Manipur.

- Wildlife Institute of India (2022–23) conservation plan reports critically low wild population and severe habitat fragmentation.

- Raises questions on wetland governance, hydropower–ecology conflict, and species-specific conservation failures.

Relevance

GS III – Environment & Biodiversity

- Endangered species conservation.

- Wetland ecology (Ramsar sites).

- Protected Area management failures.

GS I – Geography (India)

- Loktak Lake.

- Floating wetlands (phumdis).

Species Profile

- Common name: Sangai / Dancing Deer

- Scientific name: Rucervus eldii eldii

- IUCN status: Endangered

- State animal: Manipur

- Habitat specificity: Only wild population confined to floating meadows of Keibul Lamjao National Park

- Unique feature:

- Brow tine on forehead (males).

- Delicate gait over floating vegetation → “dancing” illusion.

Geographical & Ecological Context

- Located in Imphal Valley, south of Loktak Lake.

- Keibul Lamjao NP:

- World’s only floating national park.

- Ramsar Convention site (Wetland of International Importance).

- Core ecological unit: Phumdis

- Floating mats of vegetation + organic matter.

- Must be ≥1 metre thick to support adult Sangai (90–115 kg).

Population Status & Data

- Declared extinct: 1951 → rediscovered later.

- Apparent recovery till 1984, followed by decline.

- WII (2022–23) findings:

- ~64 individuals in the wild.

- ~200 in captivity (zoos across India).

- Earlier census (2016) showing 260 individuals now believed to be inflated / methodologically weak.

- Habitat squeezed to ~10 sq km → severe crowding.

Key Threats

1. Habitat Collapse (Primary Driver)

- Phumdis thinning & fragmentation due to:

- Altered hydrology.

- Pollution load.

- Observed impact:

- 2023 census: 2 Sangai + 4 hog deer carcasses recovered → probable drowning.

2. Hydropower–Wetland Conflict

- 1983 downstream multipurpose hydroelectric project:

- Causes monsoon backflow into Loktak–Keibul system.

- Leads to:

- Erosion of phumdis.

- Delay in regeneration of floating mats.

- Altered nutrient cycles.

3. Pollution & Urban Pressure

- Untreated sewage from towns enters lake.

- Excess nutrients → disrupt endemic plant species anchoring phumdis.

4. Genetic & Demographic Risks

- Inbreeding depression due to:

- Extremely small effective population.

- Habitat confinement.

- Results:

- Reduced fertility.

- Higher disease susceptibility.

- Lower long-term viability.

5. Institutional Gaps

- Ramsar status without effective wetland hydrological management.

- Fragmented responsibility: wildlife, water resources, power departments.

Governance & Policy Dimension

- Protected Area ≠ Protected Ecosystem

- Focus on species protection, neglect of ecosystem processes.

- Lack of environmental flow norms for Loktak basin.

- Absence of integrated lake–river–wetland authority.

Environmental & Climate Dimension

- Phumdis are climate-sensitive:

- Changing rainfall patterns amplify hydrological stress.

- Loss of floating wetlands:

- Carbon sequestration declines.

- Biodiversity collapse (hog deer, fish, birds affected).

Security & Cultural Dimension

- Sangai = cultural keystone species of Manipur:

- Embedded in dance, art, sports ethos, and identity.

- Biodiversity loss risks:

- Cultural alienation.

- Local resistance to conservation if livelihoods ignored.

Way Forward

Ecological Measures

- Restore minimum phumdi thickness through:

- Controlled water levels.

- Nutrient balance restoration.

- Native vegetation regeneration programs.

Hydrological Governance

- Enforce environmental flow regime downstream of hydropower project.

- Seasonal water-level modulation aligned with phumdi regeneration cycle.

Genetic Conservation

- Scientific metapopulation strategy:

- Carefully managed translocations.

- Genetic exchange between captive and wild populations (where viable).

Institutional Reform

- Loktak–Keibul Integrated Wetland Authority:

- Wildlife + Water + Urban governance convergence.

- Community-based wetland stewardship with local fishers.

Monitoring & Science

- Annual independent population audits using modern methods (camera traps, genetic sampling).

- Long-term ecological research station at Keibul Lamjao.

Prelims Pointers

- Keibul Lamjao NP = only floating national park in the world.

- Sangai subspecies = Rucervus eldii eldii.

- Phumdis must be ≥1 m thick to support Sangai.

- Loktak Lake = Ramsar site + hydropower-linked wetland.