Published on Nov 3, 2025

Daily Editorials Analysis

Editorials/Opinions Analysis For UPSC 03 November 2025

Content

- The vision of Model Youth Gram Sabhas

- Cruising ahead

The vision of Model Youth Gram Sabhas

Why in News ?

- The Ministry of Panchayati Raj, in collaboration with the Ministries of Education and Tribal Affairs and the Aspirational Bharat Collaborative, launched the Model Youth Gram Sabha (MYGS) 2025.

- Aim: To cultivate civic participation, local leadership, and awareness of Panchayati Raj Institutions (PRIs) among students by simulating real Gram Sabha proceedings.

Relevance:

- GS-2 (Governance & Polity): Local governance, participatory democracy, 73rd Amendment.

- GS-1 (Society): Role of youth and civic engagement in nation-building.

Practice Question :

- Discuss how the Model Youth Gram Sabha initiative can strengthen the democratic fabric of India by bridging the gap between constitutional ideals and civic practice.(150 Words)

Constitutional & Institutional Basis

- Article 243A (73rd Constitutional Amendment Act, 1992):

Empowers the Gram Sabha to function as the foundational body of the Panchayati Raj System. - Definition: Comprises all registered voters of a village; deliberates on local budgets, plans, and governance priorities.

- Significance:

- Embodies direct democracy.

- Ensures transparency, accountability, and citizen participation at the grassroots.

Gram Sabha – Cornerstone of Participatory Democracy

- Role in Democratic Architecture:

- Equivalent in importance to Lok Sabha and Vidhan Sabha, but at the village level.

- Represents the purest form of democracy—citizens directly deliberate on governance.

- Current Challenge:

- Low public participation; especially minimal youth engagement.

- Poor visibility in educational curricula compared to global institutions like the Model United Nations (MUN) or Youth Parliament.

Why the Gram Sabha Isn’t Aspirational ?

- Educational Gap:

- School syllabi emphasize national and international governance structures, ignoring local self-governance.

- Perception Problem:

- Youths aspire to Parliament, not Panchayats; governance is seen as top-down.

- Cultural Disconnect:

- Civic education treats the Gram Sabha as an administrative formality, not a living democratic experience.

Model Youth Gram Sabha (MYGS), 2025 – Key Features

- Objective:

- To make Gram Sabha participation experiential and aspirational among students.

- To instil democratic values and civic responsibility at an early age.

- Structure & Simulation:

- Students play roles of Sarpanch, ward members, health workers, engineers, etc.

- Simulate budget discussions, policy resolutions, and village development planning.

- Supported by teacher training and performance incentives (certificates, awards).

- Phase 1 Implementation (2025):

- Coverage: 1,000 schools across 28 States and 8 Union Territories.

- Institutions:

- 600+ Jawahar Navodaya Vidyalayas (JNVs)

- 200 Eklavya Model Residential Schools (EMRSs)

- Selected Zilla Parishad Schools (e.g., Maharashtra)

- Teacher Training:

- 126 Master Trainers

- 1,238 Teachers trained (24 States/UTs).

- Pilot Successes:

- JNV Baghpat (U.P.) and EMRS Alwar (Rajasthan) conducted successful pilots.

- JNV Sitapur (Bundi, Rajasthan) involved 300+ students in mock deliberations.

Planned Expansion (Phase 2)

- Nationwide scale-up to include all state-run schools.

- Integration into civics curricula and extracurricular clubs.

- Collaboration with NCERT, NIOS, and State Education Boards for curricular embedding.

Pedagogical & Civic Significance

- Experiential Learning: Converts textbook civics into lived democratic practice.

- Leadership Incubation: Encourages youth leadership, teamwork, and critical debate.

- Local Governance Awareness: Builds appreciation for Panchayati Raj Institutions.

- Civic Values: Reinforces the constitutional ideals of participation, inclusion, and responsibility.

Broader Democratic Implications

- Bridging the Governance Gap:

- Connects citizens to governance at the most immediate level—village decision-making.

- Institutional Continuity:

- Youth familiar with Gram Sabha functions are more likely to engage in real ones later.

- Towards Viksit Bharat @2047:

- Strengthens bottom-up governance, key for achieving inclusive and sustainable development.

- Complementary to Other Initiatives:

- Aligns with National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 (experiential learning, civic education).

- Supports Aspirational District Programme by nurturing local changemakers.

Challenges & Way Forward

- Challenges:

- Need for standardized curriculum integration.

- Varying levels of teacher capacity across states.

- Sustaining student enthusiasm beyond simulation.

- Way Forward:

- Institutionalize MYGS in school civics clubs.

- Include evaluation metrics for civic participation.

- Strengthen linkages with actual Gram Sabhas for field exposure.

- Recognize student participation in national awards and scholarships.

Comparative Insight

- Model United Nations (MUN) → Builds global awareness.

- Model Youth Parliament → Builds national political literacy.

- Model Youth Gram Sabha (MYGS) → Builds grassroots democratic consciousness.

- Complements top-down democratic learning with bottom-up engagement.

Conclusion

- The Gram Sabha is the soul of India’s democracy, yet under-recognized.

- The Model Youth Gram Sabha revives this spirit by linking youth aspiration with local governance.

- By nurturing civic pride, participatory values, and local leadership, it transforms democracy from a constitutional concept to a daily practice.

- As future leaders emerge from classrooms that simulate real governance, the Gram Sabha could once again become the beating heart of Indian democracy.

Cruising ahead

Why in News ?

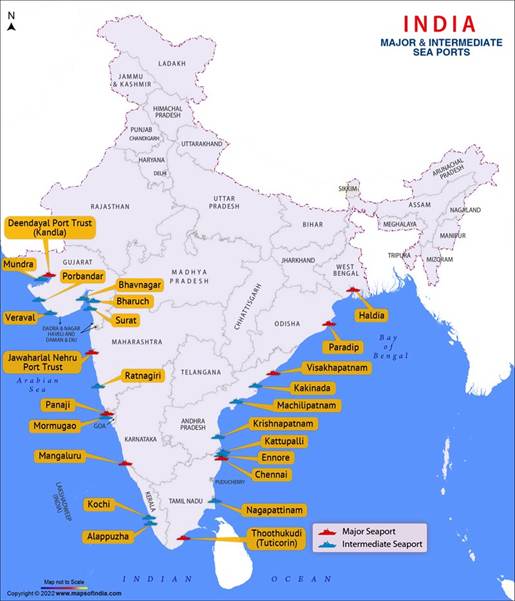

- The India Maritime Week 2025, inaugurated by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, underscored the government’s renewed focus on the strategic and economic importance of India’s shipping sector.

- The event marked a shift from decades of neglect under liberalisation policies to viewing shipping as critical to national security, trade sovereignty, and industrial capacity.

Relevance:

- GS-3 (Infrastructure, Economy, Maritime Transport) – Port-led development, Sagarmala, Atmanirbhar Bharat.

- GS-2 (Governance) – Strategic autonomy and public sector role in critical infrastructure.

Practice Question :

- Critically assess the impact of liberalization policies on India’s shipping sector and how recent policy interventions seek to restore strategic autonomy.(250 Words)

Background: Evolution and Decline of Indian Shipping

- Pre-liberalisation (1950s–1980s):

- India built strong public sector capabilities through the Shipping Corporation of India (SCI).

- SCI was among the top global shipping companies, owning large fleets servicing India’s oil, coal, and trade sectors.

- Post-liberalisation decline (1990s–2010s):

- Under LPG reforms, government withdrew preferential treatment to SCI (e.g., first rights on oil transport).

- Private sector entry did not compensate for shrinking public fleet capacity.

- The government’s focus shifted toward training Indian seafarers for global employment, not domestic shipping growth.

- Result: By 2020, India’s share in global shipping tonnage dropped below 1%, while dependence on foreign vessels surged.

COVID-19: A Strategic Wake-Up Call

- The pandemic exposed India’s maritime vulnerability:

- Over 90% of India’s trade by volume and 70% by value depends on shipping.

- But most vessels were foreign-owned, leaving India with little leverage to ensure supply chain continuity.

- The crisis highlighted shipping as not just an economic sector but a strategic asset, vital for energy security, defense logistics, and trade resilience.

Government’s Renewed Maritime Focus

- Strategic Repositioning:

- Shipping is now treated as “dual-purpose infrastructure” — economic + strategic.

- SCI revival: Fleet expansion, fleet modernization, and new capital infusion after the aborted privatization plan.

- Policy Orientation Shift:

- From a purely market-liberal approach to strategic interventionism.

- Aim: Develop self-reliant merchant shipping aligned with Atmanirbhar Bharat and Maritime India Vision 2030.

Major Announcements at India Maritime Week

- Port-Centric Investments:

- Lakhs of crores in investment commitments — mainly in port modernization and connectivity.

- Government follows the Landlord Port Model:

- Ports retain ownership; private operators handle terminals under revenue-sharing.

- Enhances financial autonomy for reinvestment in capacity building.

- New Transshipment Hubs:

- Chennai Port and Kolkata Port developing a hub in the Andaman & Nicobar Islands to reduce reliance on Singapore/Colombo.

- Sagarmala & Bharatmala Synergy:

- Focus on port-road-rail integration, coastal cargo corridors, and logistics parks.

- Human Capital Development:

- Expansion of Indian seafarer training capacity to maintain India’s global leadership (Indian seafarers form ~10% of global maritime workforce).

Policy Initiatives for Shipping Industry

- Flagging Incentive Scheme:

- Encourages foreign companies to register ships in India via local subsidiaries.

- Objective:

- Ensure regulatory leverage during crises.

- Support allied services — insurance, repair, logistics, bunkering.

- Fleet Expansion Support:

- New credit lines and tonnage tax reforms to enhance Indian ship ownership.

- Shipbuilding Push:

- Slow progress despite policy intent.

- Government aims to promote domestic shipyards for building:

- LNG carriers,

- Green-fuel (ammonia/methanol) vessels,

- Defence dual-use ships.

Structural Challenges

- Low Merchant Fleet Share: India-owned fleet constitutes <2% of cargo handled in Indian ports.

- Shipbuilding Weakness:

- India ranks behind China, Japan, South Korea in global shipbuilding output.

- Limited heavy industrial capacity and R&D for advanced propulsion systems.

- Financing Constraints:

- High capital costs and long project cycles deter private investment.

- Policy Uncertainty:

- Frequent regulatory changes, port user charges, and taxation issues limit competitiveness.

Strategic Importance of a Strong Shipping Sector

- Trade Security: Control over transport of critical imports (oil, fertilizers, defense materials).

- Economic Multiplier: Boosts allied industries — steel, engineering, insurance, logistics.

- Energy Transition Leverage: Capability to build LNG and green-fuel vessels essential for future trade.

- Geopolitical Stability: Maritime capacity enhances India’s position in Indo-Pacific strategic supply chains.

The Road Ahead: Policy Recommendations

- Revive and modernize SCI with a diversified fleet mix.

- Fiscal incentives for private shipbuilders (interest subvention, long-term contracts).

- Green Shipping Initiative under National Hydrogen Mission for eco-friendly propulsion systems.

- Maritime Cluster Development: Create integrated hubs combining shipbuilding, repair, logistics, and R&D.

- Expand coastal shipping and inland waterways to decongest ports and reduce logistics costs (currently ~14% of GDP).

Conclusion

- India’s maritime strategy is shifting from port-centric to fleet-centric development.

- Without strong indigenous ship ownership and shipbuilding, India risks dependence in crises despite having world-class ports.

- True maritime power will emerge when Indian yards can build and operate advanced green vessels, and India controls a self-reliant merchant fleet serving both commercial and strategic needs.