Contents :

- Sustainability Science for FMCGs in India

- The private sector holds the key to India’s e-bus push

- Beyond intoxication

Sustainability Science for FMCGs in India:

Context: Anusandhan National Research Foundation (ANRF) and BioE3 (Biotechnology for Economy, Environment, and Employment) policy highlights a commitment to encourage academia-industry partnerships aimed at developing sustainable, bio-based alternatives. especially within the Fast-Moving Consumer Goods (FMCG) sector.

Relevance: GS 3 ( Environment )

Practice question: Examine the impact of palm oil production on biodiversity. What measures can be taken to mitigate these effects, and what steps has India implemented to address these challenges? (250 words)

What are FMCG?

FMCG stands for Fast-Moving Consumer Goods. These are products that are sold quickly and at relatively low cost. FMCG items are typically those which are essential or frequently purchased by consumers due to their high demand and shorter shelf life. Its market projected to reach around $220 billion by 2025

Example: Food and beverage, Household products, etc

India’s Bio-Economy Focus:

- ANRF and BioE3 Policy: These initiatives aim to transition from chemical-based industries to bio-based models. The goal is to integrate sustainable development into economic progress by emphasising research and innovation.

- Academia-industry partnership: It’s important to address sustainability challenges and gaps in adoption through utilising biotechnologies and promoting self-reliance by focusing on research and development.

Palm Oil in FMCGs:

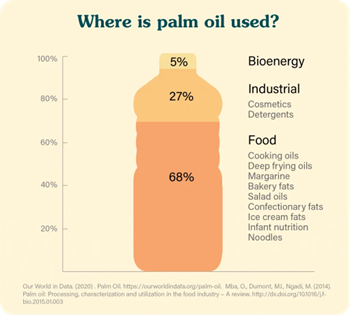

- Palm oil is commonly used in FMCGs due to its versatility and cost-effectiveness. It’s found in products like snacks, baked goods, soaps, shampoos, and detergents.

- Environmental Concerns: Palm oil, widely used in soap production, is linked to deforestation and biodiversity loss, with plantations often replacing ecologically forests.

For instance: According to a study published in PLOS ONE, 45% of sampled oil palm plantations in Southeast Asia originated from areas that were forests in 1989.

- Yield Efficiency and Demand: High yield and low cost make palm oil attractive, meeting roughly 40% of global vegetable oil demand.

Technological Alternatives to Palm Oil:

- Synthetic Biotechnology Solutions: Advanced biotechnologies could be utilised to replicate the structural aspect of palm oil.

e.g. Utilising engineering microbes to produce oils with characteristics of palm oil.

- Local Bio-based Alternatives: Potential substitutes include plant-based polysaccharides and antimicrobial peptides, which could replace palm oil-derived components while enhancing soap benefits (e.g., boosting skin immunity).

Value Chain Support and Government Role:

- Policy-backed Innovation: ANRF and BioE3 could support innovations that integrate plastic-free packaging.

- Need for Civil Society Involvement: Industry players, researchers, and consumers all play a role in promoting a shift toward sustainable FMCG solutions.

- Cost Implications: Sustainable practices can raise production costs, which are passed to consumers, affecting the product’s market competitiveness.

- Sustainability Ratings: Product labelling based on sustainable sourcing and production can encourage consumers to make informed choices aligned with environmental values.

Domestic Palm Oil Production:

- National Mission on Edible Oils-Oil Palm: India’s 2021 initiative seeks to increase palm oil production while adhering to sustainable standards (e.g., ‘No Deforestation, No Peat’).

- Mission aims to increase the oil palm production area to 10 lakh ha. and boost crude palm oil production to 11.20 lakh tonnes by 2025-26.

Conclusion:

The integration of ANRF and BioE3 policies sets a foundation for a bio-based economy that respects ecological limits and emphasises innovation. Innovation and research will make the transition smoother.

The Private Sector Holds The Key To India’s E-Bus Push

Context: The PM Electric Drive Revolution in Innovative Vehicle Enhancement (PM E-DRIVE) scheme has been approved by the Union Cabinet, allocating ₹4,391 crore for electric vehicle (EV) incentives, particularly focusing on the procurement of 14,028 electric buses across nine cities.

Relevance: GS3 (Environment )

Practice question: How can the private sector contribute to India’s electric bus adoption? Suggest steps the government can take to support private operators in this transition. (150 words )

Current scenario :

- Public Sector Dominance: The deployment of electric buses has primarily been driven by public sector initiatives, particularly through the FAME India scheme.

- Under FAME I (2015-2019), 425 buses were subsidised, which increased significantly to 7,120 buses under FAME II (2019-2024).

- However, public transport buses constitute only 7% of the total 24 lakh registered buses in India, highlighting the limited scope of public sector efforts.

- Exclusion of Private Sector: The majority of buses (93%) in India are privately owned, yet these operators are excluded from major national schemes or incentives.

- Financing Hurdles: Factors such as high upfront costs, perceived risks, and low resale value of electric buses complicate access to loans.

Market Potential for Inter-city Electric Buses :

- The inter-city bus sector serves 22.8 crore passengers daily, accounting for 57% of total ridership and 64% of vehicle kilometres.

- Notably, 40% of intercity trips are within the 250 km to 300 km range, which aligns well with the range capabilities of current electric bus models.

Recommendations for Policy Support :

- To facilitate the transition to electric buses, the ICCT report suggests offering favourable financing options, such as credit guarantees, interest subsidies and extended loan tenures, to mitigate financial risks.

Infrastructure Challenges :

- Charging Infrastructure: Limited access to charging facilities hinders electric bus adoption. Current FAME-funded facilities cater primarily to state transport units, neglecting the needs of private operators.

- Given that 90% of private bus operators manage fleets of fewer than five buses, the high costs associated with establishing charging infrastructure pose significant challenges.

Emerging Business Models :

- The Battery-as-a-Service (BaaS) model, which separates battery ownership from vehicle ownership, could significantly lower the initial investment required for electric buses.

- Battery swapping and usage-linked leasing models, already successfully implemented in countries like China and Kenya, present viable solutions for accelerating private electric bus adoption.

Conclusion

The PM E-DRIVE scheme offers great opportunities for policymakers to address financing barriers, enhance charging infrastructure, and explore innovative business models that encourage private investment in electric buses.

Beyond Intoxication

Context: Recently Supreme Court clarified the term ‘intoxicating liquors’ under State List Entry 8 includes all types of alcohol (potable and industrial).

Relevance: GS2 ( Indian Polity )

Practice Question: How does the recent Supreme Court ruling on alcohol regulation strengthen the federal structure in India? Explain its impact on state and central powers. (250 words )

Federal Balance and State Powers:

- State Authority: Judgment reinforces state authority to regulate both potable and industrial alcohol.

- Limitation on Union Control: Prevents the Union from regulating the ‘intoxicating liquor’ industry under the Industries (Development and Regulation) Act (IDRA), 1951.

- Legislative Competence: The Supreme Court held that Parliament lacks authority over the entire alcohol industry, safeguarding states’ rights.

- Federal Principle: Chief Justice D.Y. Chandrachud’s opinion emphasised maintaining the federal balance, preventing Union overreach into state matters.

- Supporting State Autonomy: Aligns with recent judgment allowing states to tax mineral resources, signalling support for state autonomy.

- Economic Perspective: Justice Nagarathna viewed ‘intoxicating liquors’ as referring only to potable alcohol, allowing the Centre control over industrial alcohol.

- Economic Importance: Highlights industrial alcohol’s significance in chemicals and energy, arguing for a cautious approach to constitutional interpretation.

Impacts and Implications:

- Federal Autonomy Reinforced: The decision highlights the Supreme Court’s role in protecting state powers and upholding the Constitution’s federal structure.

- Balancing Growth with Federalism: Reflects a nuanced balance between economic priorities and constitutional boundaries.

- Precedent for State Rights: Establishes a precedent for similar disputes where state regulatory powers intersect with central frameworks.

- Potential Impact on Other Sectors: This may influence federal debates in minerals, agriculture, and other areas where economic interests and state autonomy converge.

Conclusion:

This judgment reaffirms state jurisdiction over alcohol regulation, upholds federal principles, and demonstrates the judiciary’s commitment to protecting state legislative authority against central overreach.